Theory Evolution

Introduction

The Spectrum today is a more expanded theory than it was in 1966. Each of the topics presented in this section are new discoveries, clarifications, or insights that gradually revealed the complex network and its multiple component parts that are always embedded within and necessary for all teaching and learning. By linking theory to implementation, we observed that when any component part was omitted, the system did not properly function.

The Spectrum's unravels the complicated structure intrinsic to pedagogy. Although T-L will remain complex and seemingly mysterious, it possesses an intrinsic network with a predictable structure and a solid yet ever-evolving knowledge base. This network does not restrict options, rather it offers unlimited developmental opportunities from Command to Discovery.

Theory Overview

This section presents changes in the Spectrum theory since its inception in 1966.

First, which key features have remained unchanged?

- Muska's discovery that a single governing principle underlies every teaching-learning event remains unchanged. That principle is, the axiom of the Spectrum: Teaching is a chain of decision making.

- Additionally, The Anatomy of Any Style continues to provide the framework for the conceivable categories of decisions that must be made in any teaching-learning transaction. The specific configuration of the Anatomy’s decisions in each set determines the specific teaching-learning approach. Every landmark T-L approach has a unique decision pattern in the three sets of the Anatomy. Each canopy T-L approach shares a blended decision configuration with other styles.

Second, which features in the Spectrum have changed?

Changes were made when the actions during classroom implementation did not fully correspond with the theory. While some discrepancies (theoretical gaps) required only minor adjustments, other discrepancies required years of investigation to find the missing link between the theoretical intent and classroom practice.

The following topics highlight some of the changes, additions, or refinements to the theory.

Name Changes

A major misconception about the theory is that its primarily focuses on teacher behavior rather than the student's learning process (Metzler, On Style, 1983, 35, 145-154). This assertion is incorrect. The Spectrum concepts reinforce the inherent purpose of teaching – to optimize learning. The Spectrum delineates a range of significantly different teaching and learning options (styles) from Command to Discovery, and each style is defined by a specific decision pattern for both the teacher and learner so that specific landmark learning expectations can be offered.

The style names are not arbitrary or for poetic purposes. Each style name indicates the students' anticipated learning focus.

Note: Because some of the style names changed during the early years, the letters associated with the styles became confusing; therefore, the styles are now referred to in print by both name and letter.

Command Style-A

The original name, Command, accurately captures the essence of the student's learning focus in this landmark style. However, this name has stirred controversy and misunderstanding. Historically, the name has been primarily connected to a behavior of an authority figure commanding instructions. In the Spectrum this term refers to the learners’ behavior to command their own thinking to develop automaticity and precision in content performance. The specific decision configuration in this style establishes a learning focus that challenges students to cognitively achieve content acquisition with such precision that automaticity becomes the ultimate performance expectation.

In other words, the students in this landmark style develop the ability to command their thinking to achieve automaticity and precision performance along the Developmental Channels that the task requires. The essence of this landmark style is to replicate, with precision, even with automaticity a task within a short period of time. The landmark style is not designed to foster passive or inactive experiences. Reinforcing immediate memory acquisition is the content objective.

Practice Style-B

Prior to the 1981 publication (in the 1966 and 1972 editions) Practice Style-B was called Task Style. There were two reasons for the name change to the Practice Style.

- First, all styles have a task, and the name task style was too ambiguous to represent one specific style.

- Second, we discovered that the term, practice, inherently relies on the decision structure and the nine decisions of Style-B. Therefore, the term Practice Style more accurately represents the learning focus of Style-B, which is to practice making nine decisions while engaging in a task.

SIDE NOTE: This change in style name from Task to Practice originated in 1970 during a workshop at a large high school in New Jersey. During the microteaching phase of our workshop, a teacher who had difficulty naming the nine decisions to her students lumped the decisions together and said, “Go practice these math problems.” It was a eureka Moment for us—she revealed an association of a common term with its inherent decision structure.

Note: although the term, practice, accurately links to the decision structure and expectations of Style-B, the name is still ambiguous because ALL reproduction styles (A-E) are practice styles with different task and feedback expectations. Perhaps the most accurate name for this landmark style is: Individual Practice Style-B.

Reciprocal Style-C

Two styles in the 1966 text were merged in1972. After numerous classroom implementation experiences, we observed that the two styles, Reciprocal Teaching – the Use of the Partner and The Use of the Small Group, shared the same decision anatomy. These styles primarily differed in logistics-the number of students that worked together.

We discovered that in these two styles the number of students in a partnership did not change the decision configuration or the behavior expectations.

In Style C, the learners work in a partnership, one partner practices a task while the other offers performance feedback using the established teacher-prepared criteria. At a given point, the partners switch roles. Consequently, the name of this style is Reciprocal Teaching. The learning focus is to learn to compare and contrast the accuracy of performance using criteria.

Self-Check Style-D

This style was first described in the 1981 edition. Previously, Self-Check behavior had been associated with the Reciprocal Style. While observing classroom interactions, it became clear that the decision anatomy and objectives of the Reciprocal and Self-Check Styles were significantly different. Offering feedback to self is developmentally different from offering feedback to a partner. Hence, Self-Check became a separate style that developed independent practice and self-assessment using criteria as well as perseverance and honesty.

Inclusion Style-E

The Inclusion Style-E provides opportunities for students to practice a task at their chosen level of difficulty and to self-assess their performance using established teacher-prepared criteria. The decision anatomy and the set of objectives in this decision relationship are significantly different from Styles B, C or D. The Inclusion Style-E was originally named the Individual Program (1966, 1972). The term, Individual Program, was replaced because all styles can make use of an individual program. The Inclusion Style specifically focuses on the opportunities for continued participation of the learners because they can select their level of difficulty and engage in self-assessment using a criterion. Each teaching style indicates expectations for the teacher. The Inclusion Style requires teachers to prepare content materials with different degrees of difficulty in the same task so that all learners can be continuously included in the practice of the same subject matter task.

(The Inclusion Style-E is not assigning different students to different subject matter tasks. This behavior (decision pattern) is akin to Style-B.)

How Styles A-E Differ from Styles F-K

Two basic thinking capacities are reflected within the structure of the Spectrum: the capacity for reproduction (memory thinking) and the capacity for production (discovery thinking). Styles A-E form a cluster of T-L options that foster different reproduction thinking about existing information and knowledge. The remaining Styles F-K form a cluster of T-L options that invite different discovery thinking options which focus on the production of new knowledge. Each discovery style delineates a different discovery pattern. The name of these styles reflects the pattern of discovery the learners will engages in while discovering new content.

Guided Discovery Style-F

This style name has remained the same in all text editions. It represents one pattern of discovery using a series of deliberately sequenced questions that lead to one and only one anticipated response to be discovered.

Convergent Discovery Style-G

Convergent Discovery Style-G first appeared in a 1990 text. Our classroom implementation experiences revealed that there is more than one pattern for discovery thinking. Not all discovery experiences shared the same thinking pattern. Guided Discovery-F and Convergent Discovery-G are similar in that they both seek a convergent process--one anticipated correct response. However, the thinking pattern that leads to the discovered response is different in each style.

The Convergent Discovery Style-G poses only a single question while Guided Discovery Style-F relies on a series of logically connected questions. Convergent Discovery engages each individual learner to search for content that links and leads to solving the question. The learners design the questions and the answers that lead and link to the convergent discovery.

Divergent Discovery Style-H

This style name changed several times from Problem Solving (1966, 1972) to Divergent Style (1981, 1986) to The Divergent Production Style (1990, 1994) and then finally to Divergent Discovery Style (2002).

The previous names were ambiguous in that they did not uniquely and accurately indicate the essence of the learning focus in his style. Divergent thinking seeks multiple responses (as opposed to convergent thinking that merges responses to one). The name Divergent Discovery-H delineates the learner’s learning experience in this style, which is for each learner to discover multiple, divergent responses.

The remaining styles on the Spectrum

A distinction in the decision configuration (the O-T-L-O) among the remaining styles occurred over many years. Each style contributes differently to the process of developing independence. No one set of decisions within the various teaching-learning styles represents or totally develops independence. All styles contribute to and emphasizes different dimensions necessary for the development of independence.

Learner-Designed Individual Program Style-I

This name first appeared in the 1986 text. Although the term, individual program, can be applied to any style, this style name does indicate the specific three-fold learning focus of Style-I. First, the individual learner's ideas are the focus. The teacher indicates only the general content focus. Second, the program involves sustained engagement and is a program with multiple connecting parts instead of a single task or a series of individual tasks. Third, it’s Learner Designed, which means that the content specifics are produced by the learner instead of recalled by the learner. This style name, The Individual Program - Learner's Design Style-I, emphasizes the opportunity for individuals to design and produce conceptual ideas and programs.

Learner Initiated Style-J

This name first appeared in the 1986 text. Learner's Initiated Style-J is the first style where pre-impact decisions are made by the learner. The shifting of the pre-impact set of decisions occurs only after a student initiates the desire to engage in this style. Learner is not plural but singular. This style is not a total class activity rather it is an experience that an individual initiates with the teacher.

This style's learning focus invites self-initiation and the development of tenacity, the ability to follow thorough and to discover and implement the various decisions that accompany the production of one's ideas. This style is about independent expression. The teacher’s involvement is established by the student.

Self-Teaching Style-K

In 1986, this style name appeared. Previously, the idea of learners assuming total independence and autonomy had been referred to as: (1) the Next Step—Creativity (1966); (2) The Individual Program (Student's Design) or Toward Creativity (1972); and (3) Going Beyond (1981). Both the current name and the specific decision anatomy (O-T-L-O) and expectations took time to evolve.

Each of the previous names contributed a portion of what this last teaching style can be. It is a style that can trigger the learner’s individuality, uniqueness, and self-expression or a search for the unknown. Self-Teaching Style-K is free of outside imposed limits and is energized by the creation and production of something new and personal. Self-Teaching is not found within the establishment called school because the decision-making process of the learner is independent of a teacher.

This style has been inaccurately viewed as the desired direction and intent for education. The Spectrum does not support that VERSUS view. No style is inherently good or bad. The decision structure in each style is devoid of value or judgment. In fact, the outcomes of this style can range from glorious to disastrous to mediocre. It can be harmless, or it can be immoral like the Columbine Massacre April 20, 1999. The selection of content and specific human attributes determines the value of this Self-Teaching experience.

The Command Style-A and Self-Teaching Style-K thus establish the bookends and extremes of the Spectrum of Teaching Styles. With these bookends and everything in between, a pedagogical continuum is created from Command to Discovery.

The Schematic Diagram

This section provides insight about the graphic designs used to represent the landmark T-L options. The first published schema (visual graphic) that represented the Spectrum framework was a cone-shaped design. This design was changed by 1967 after a student at Rutgers questioned the apparent discrepancy between the Spectrum's non-versus foundation and the value-laden cone-shaped design. This design change did not appear in print until 1981.

The cone shape was evidentially changed to two parallel lines with equal dimensions and dotted lines between the styles. In spite of the fact that Muska provided the rationale for this schematic change in the 1981 second edition, controversy continues to linger over this design change (Sicilia-Camacho, Brown, 2008). The following is Muska's rationale for the change:

"The conceptual basis of the Spectrum rests on the NON-VERSUS notion. That is, each style has its place in reaching a specific set of objectives; hence, no style, by itself, is better or best.

Each style is equally important. Each style makes an important contribution to the relationship between the teacher and the student and the developmental growth of the student. It is the sum total of the experiences in all styles that contributes to an independent person. The foundational conception of the Spectrum, the shift in thinking from VERSUS to NON-VERSUS, is apparent in all decisions related to the development of the Spectrum styles.

The following is the first visual graphic of the Spectrum.

This earlier conception was misinterpreted as assigning a very small value to Style-A, with each subsequent style having a greater value until maximum value was placed on the last style. This visual image reinforces the "versus" notion – that one style is in competition or better than others. No one style is inherently more important than another. Years of experimentation and implementations reinforced the idea that all styles are important and contribute to development. This understanding of each style's value reinforces the philosophical bases of the non-versus as a basis for an expanded pedagogy" (Viii, 1981).

Muska often reminisced about his early years in the 1960s when he was introducing the Spectrum to his colleagues. Conversations about pedagogy and multiple teaching styles were not a professional topic; therefore, Muska's ideas required an expanded way of thinking about T-L. Most were not ready for such an alternative view of teaching—change is generally greeted with resistance. And so, it was with the Spectrum.

Over the 25-year relationship between Muska and Sara, Muska's reasons for the initial cone-shaped design became apparent.

- First: the initial design was based on Muska's passion to move the profession from its primary use of command and practice-like behaviors to other T-L possibilities.

- Second, many of Muska's colleagues and a segment of the Physical Education profession at that time were resistant to the notion that students could or should make decisions and produce discovery-based ideas that often altered the established content by going beyond the rules in sports and games.

- Third, the cognitive rejection and the emotional resistance to the discovery styles added to Muska's emphasis of the discovery styles in the cone-shape design.

- Fourth, Muska used the cone-shaped design to represent the learner’s increased decision making from one style to another. Therefore, in terms of quantity of decisions, the right side of the Spectrum is greater.

Greater decision making does not mean better. However, through our implementation and research we discovered that no one style can offer maximum human development in all Developmental Channels. Each style on the Spectrum uniquely contributes to the human developmental process. The contributions of one style can serve as a foundation for other styles. The cone-shape design was replaced because it violated the philosophical foundation from which the Spectrum emerged. The Spectrum's inception is anchored in the NON-VERSUS approach to teaching and learning.

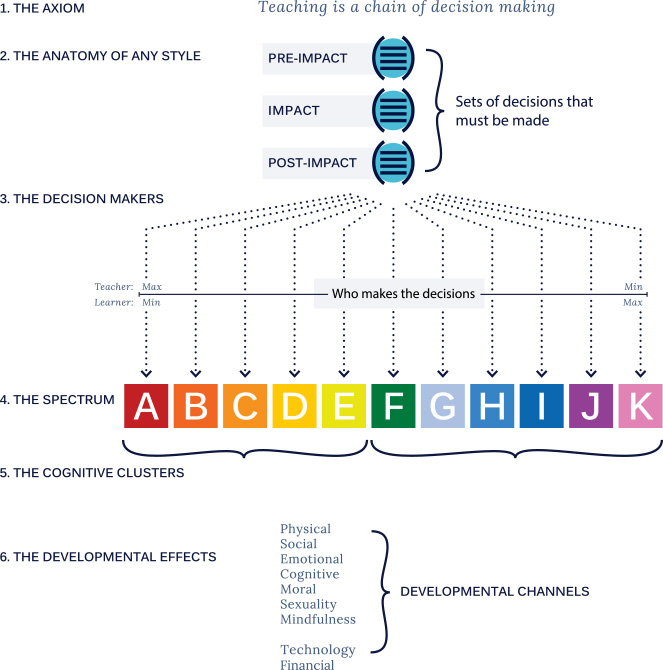

The following Figure is the current schematic overview of the Spectrum’s structure, which is based on six underlying premises.

The Axiom

The entire structure of the Spectrum stems from the initial premise that teaching behavior is a chain of decision making. Every deliberate act of teaching is a result of a previous decision.

The Anatomy of Any Style

The anatomy is comprised of the conceivable categories of decisions that must be made (deliberately or by default) in any teaching–learning transaction. These decision categories (are described in detail in the text) are grouped into three sets: the pre-impact set, the impact set, and the post-impact set. The pre-impact set includes all decisions that must be made prior to the teaching–learning transaction; the impact set includes decisions related to the actual face-to-face teaching–learning transaction; and the post-impact set identifies decisions concerning assessment of the teacher–learner transaction. The anatomy delineates the decisions that must be made in each set

The Decision Makers

Both teacher and learner can make decisions in any of the decision categories delineated in the anatomy. When most or all of the decisions in a category are the responsibility of one decision maker (e.g., the teacher), that person's decision-making responsibility is at "maximum," while the other person's (the student's) is at "minimum."

The Spectrum

By establishing who makes which decisions, about what and when, it is possible to identify the structure of 11 landmark teaching–learning approaches as well as alternative approaches that lie between these 11 styles on the Spectrum.

In the first style (Style-A), which has as its overriding objective is precision and replication. The teacher makes all the decisions; the learners respond by adhering on cue to all of the teacher's decisions. In the second style (Style-B), nine specific decisions are shifted from the teacher to the learner and, a new set of objectives in subject matter and behavior can be reached. In every subsequent style, specific decisions are systematically shifted from teacher to learner, allowing new objectives to be reached until the full Spectrum of teaching-learning approaches is delineated.

The Clusters

Two basic cognitive human capacities are reflected within the structure of the Spectrum: the capacity for reproduction and the capacity for production thinking. All human beings have, in varying degrees, the capacity to reproduce known knowledge, replicate models, and practice skills. All human beings have the capacity to produce a range of ideas, to venture into the new and to tap the yet unknown. These two capacities one limited to one pattern. There is a cluster of reproduction styles A-E and a cluster of production styles F-K Each offers an expanded cognitive experience.

The Developmental Effects

Perhaps the ultimate question in education and teaching is, “What really happens to people when they participate in one kind of an experience or another?” The questions Why and What for are paramount in education. The structure of the decisions in each landmark style affects the developing learner in unique ways by creating conditions for diverse developmental experiences. Each set of decisions in the landmark styles emphasizes distinct human objectives. Objectives, aside from the content expectations, are always related to human attributes that support cognitive, social, physical, emotion, and ethical developmental. The ability to identify the attributes highlighted in each it possible for the teacher to assess the quality and focus of each educational experience. All teaching event provides opportunities to participate in specific human attributes along the Developmental Channels. Although one channel may be more strongly in focus than others, all channels function concurrently. It is virtually impossible to isolate experiences to only one channel.

Teaching physical activities is unique in that its developmental focus always activates the physical and the cognitive channels as primary goals. Additionally, social, ethical and emotional attributes are intrinsic to games, sport and competitive events. The field of physical education inherently embraces more opportunities to emphasize and develop a wide range of human attributes along all the Developmental Channels than mot any other content area in the curriculum.

Each Developmental Channel represents human attributes. For example, attributes primarily emphasized along the social channel include cooperation, communication skills, sharing, being courteous to others, etc. Comparing, sorting, categorizing, interpreting, and imagining are capacities and attributes along the cognitive channel. The above-mentioned attributes are primarily exclusive to one channel, and other attributes are shared among all channels. All channels can promote and provide experiences that emphasize the attributes of respect, empathy, perseverance, motivation, patience, tolerance, self-control, resilience, etc. The way subject matter is designed always emphasizes (overtly or covertly) attributes on the channels. Each channel has an array of attributes that can be selected and joined with the specific content expectations to create the episode's teaching–learning focus.

Episodic Teaching

The most critical aspect of any theory is its implementation

How can teachers deliberately implement in the classroom a variety of alternative T-L behaviors? What is the thinking that supports the inclusion of multiple teaching and learning behaviors? How do teachers move from the current thinking about lesson planning to an altered design that incorporates multiple T-L experiences?

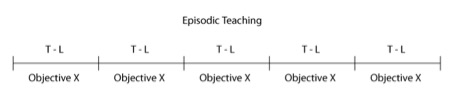

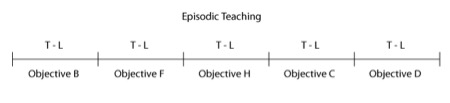

Implementing multiple approaches requires episodic teaching. An episode is a unit of time within which the teacher and learner are working on the same objective or set of objectives and are engaged in the same teaching style.

An episode might last a few minutes, an entire period, or longer. Each episode becomes the individual "unit of measure" (O-T-L-O) for what is happening in the classroom.

Each subject matter lesson is comprised of multiple parts. Each part might have a different set of objectives, different learning expectations, and different anticipated outcomes. Episodic teaching indicates a series of episodes that comprises a lesson. The series of T-L episodes can represent the same T-L style with the same…

…or similar objectives and learning expectations or it can represent different T-L styles with different sets of objectives and learning expectations.

Each lesson within the classroom period (time-frame) can be structured and viewed according to the individual episodes that comprise the lesson. Each episode can be viewed for its contributions in supporting or derailing the anticipated overall content or behavior developmental expectations. Once learners have been introduced to different style’s learning expectations, designing a series of episodes in different styles for one lesson appears seamless to learners during the flow of the lesson.

The Spectrum supports maximizing student’s learning experiences; therefore, a variety of different teaching styles need to be implemented. No single T-L behavior can accomplish all the intended content and human behavior goals of education nor can any one set of T-L behaviors meet all students' needs.

Currently, research indicates that although teachers implement a variety of classroom activities that focus on logistical, content and human developmental needs, they rarely change their predominate T-L interaction. The image of the classroom may vary (such as working individually, in groups, or whole class); however, these variations generally represent the same set of T-L decision expectations. On the other hand, in our experience, Spectrum teachers generally use different teaching styles throughout a class period.

Research

Episodic teaching is the new frontier in pedagogical research. Research that investigates one teaching style or seeks to compare the superiority of one style over another needs to be revisited. Individual style research that verifies that a teaching behavior does, what it theoretical says is worthwhile but not individual style research that pits one behavior against another. Such research does not contribute to the individual worthwhileness of a repertoire of T-L experiences. Each Spectrum landmark style offers a significantly different set of learning opportunities. The styles are not in competition. In fact each style has its own learning focus; one style does not develop another style’s objectives. Different styles develop different objectives.

Additionally, it is misleading to suggest that one style develops student’s self-concept. No one style has the capacity to develop a broad human dimension. We are all the sum total of many different T-L decisions and objectives. It is the interplay among these multiple experiences that contribute to our learning behavior. Episodic teaching can provide us with new insights about the impact that different style combinations have on learning.